Across every civilization, the vast majority of humanity’s recorded thought remains inaccessible. Tens of millions of manuscripts and printed works sit in archives, libraries, and private collections, unscanned, untranslated, or poorly catalogued. The result is a fractured intellectual record. Even as the world grows more connected, much of our history remains hidden, preventing researchers, educators, and the public from engaging with the full breadth of human knowledge.

This is not only a scholarly problem. It is a civilizational one. The texts that shaped human thought, from philosophy and science to medicine, mathematics, and esoteric traditions, remain largely unread. When knowledge is lost or inaccessible, societies inherit only fragments of their intellectual past, narrowing the context for education, culture, and innovation.

The Global Scale of Inaccessibility

Estimates show the scale of the problem: less than 10 percent of all texts written before 1800 have been digitized, over half of the world’s manuscripts remain uncatalogued, and more than 90 percent of pre-modern texts are not translated into modern languages. Only 15 to 20 percent of the world’s libraries and archives provide meaningful digital access, and UNESCO estimates that half of humanity’s documentary heritage is at risk or inaccessible.

This global “knowledge void” spans centuries and continents. It is not limited to one culture, language, or region. Every civilization contains intellectual wealth that is unavailable to those who would study, interpret, or build on it.

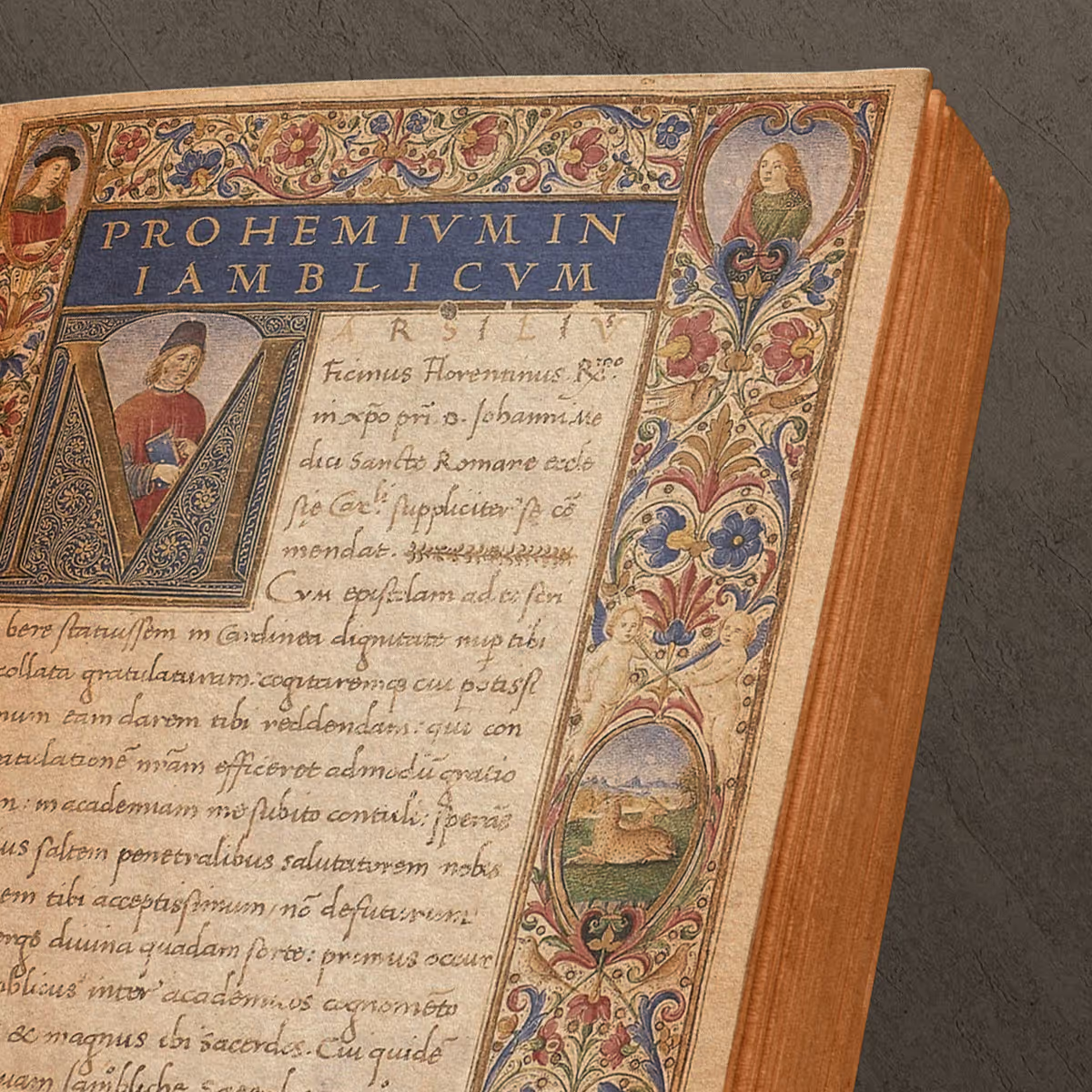

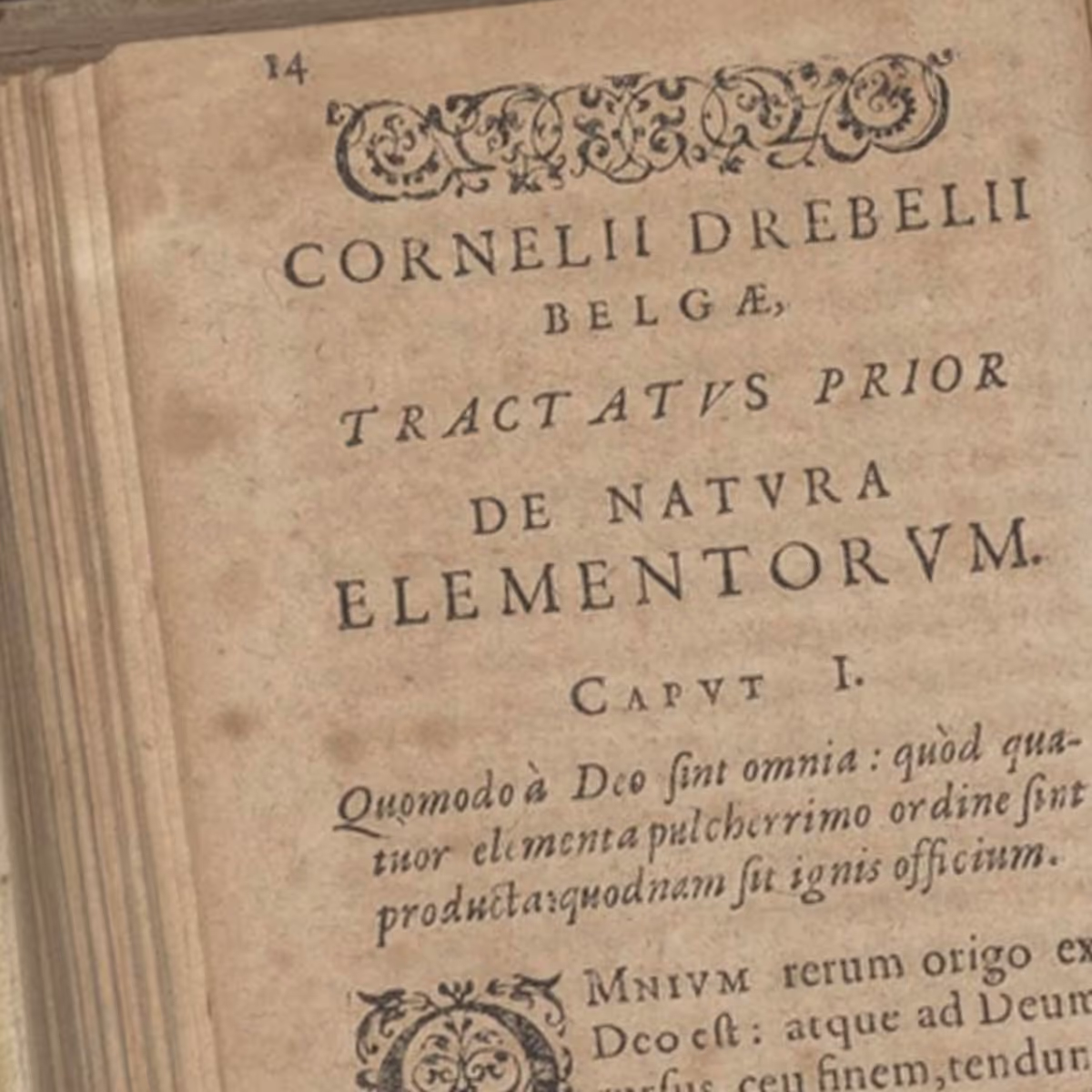

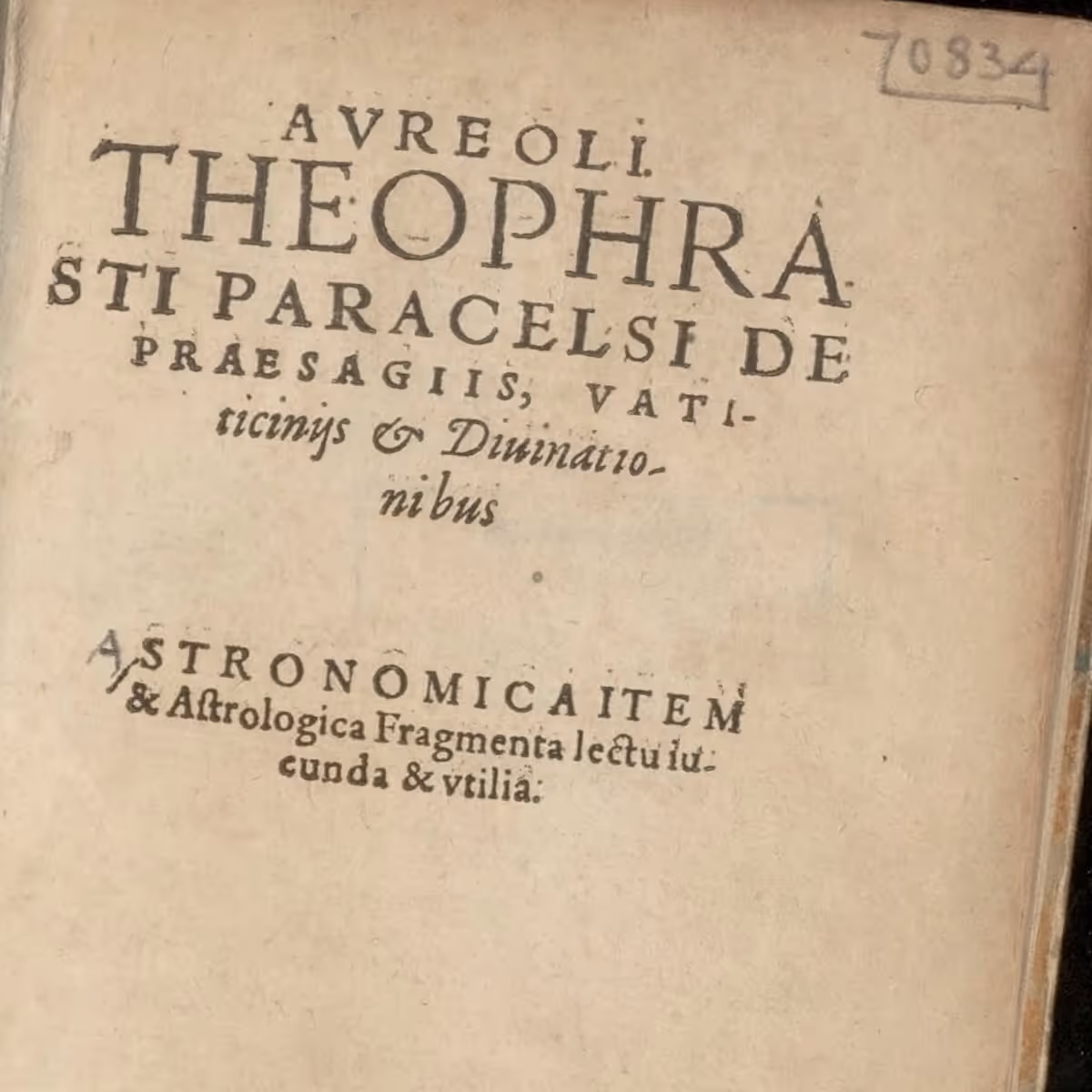

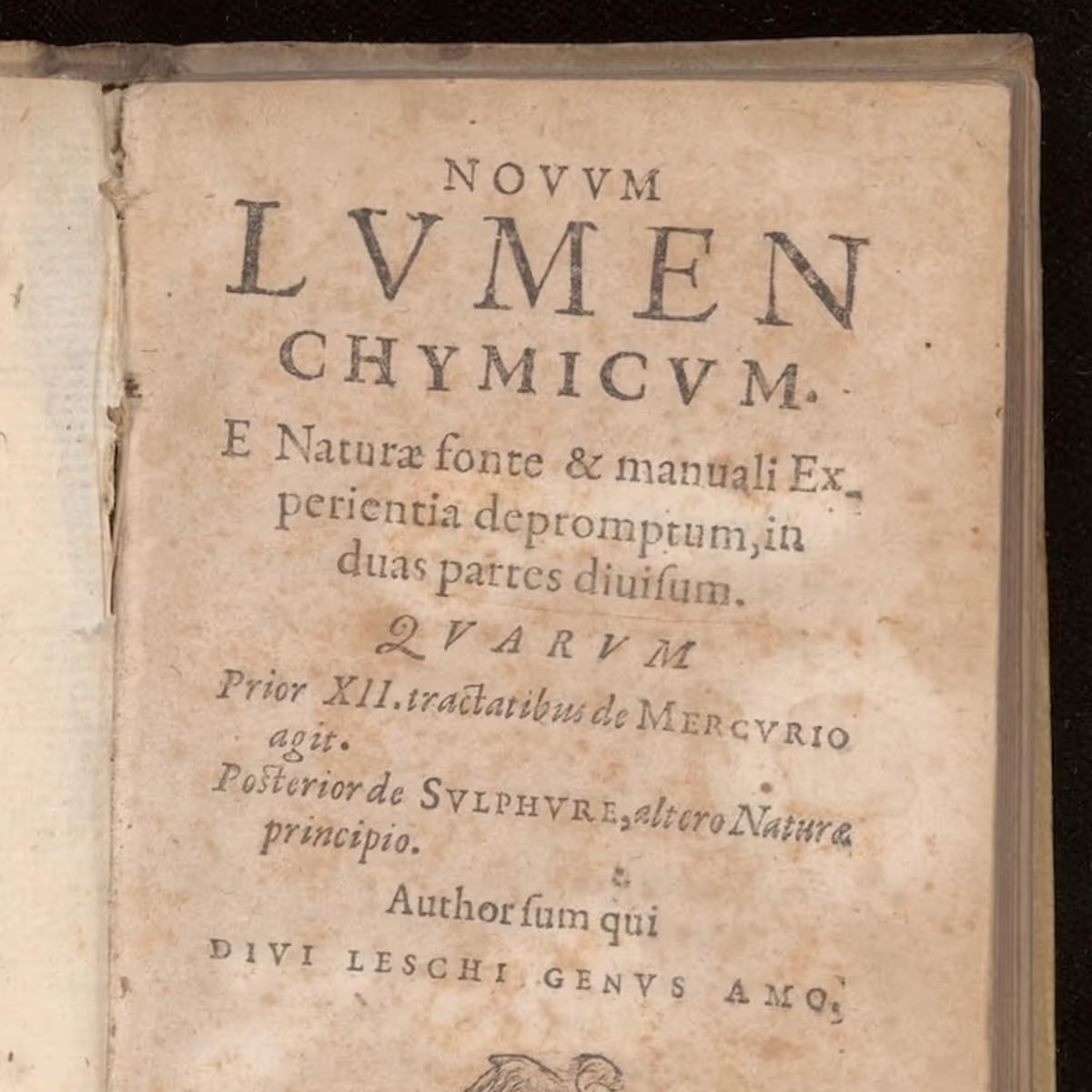

The Renaissance: A Case Study

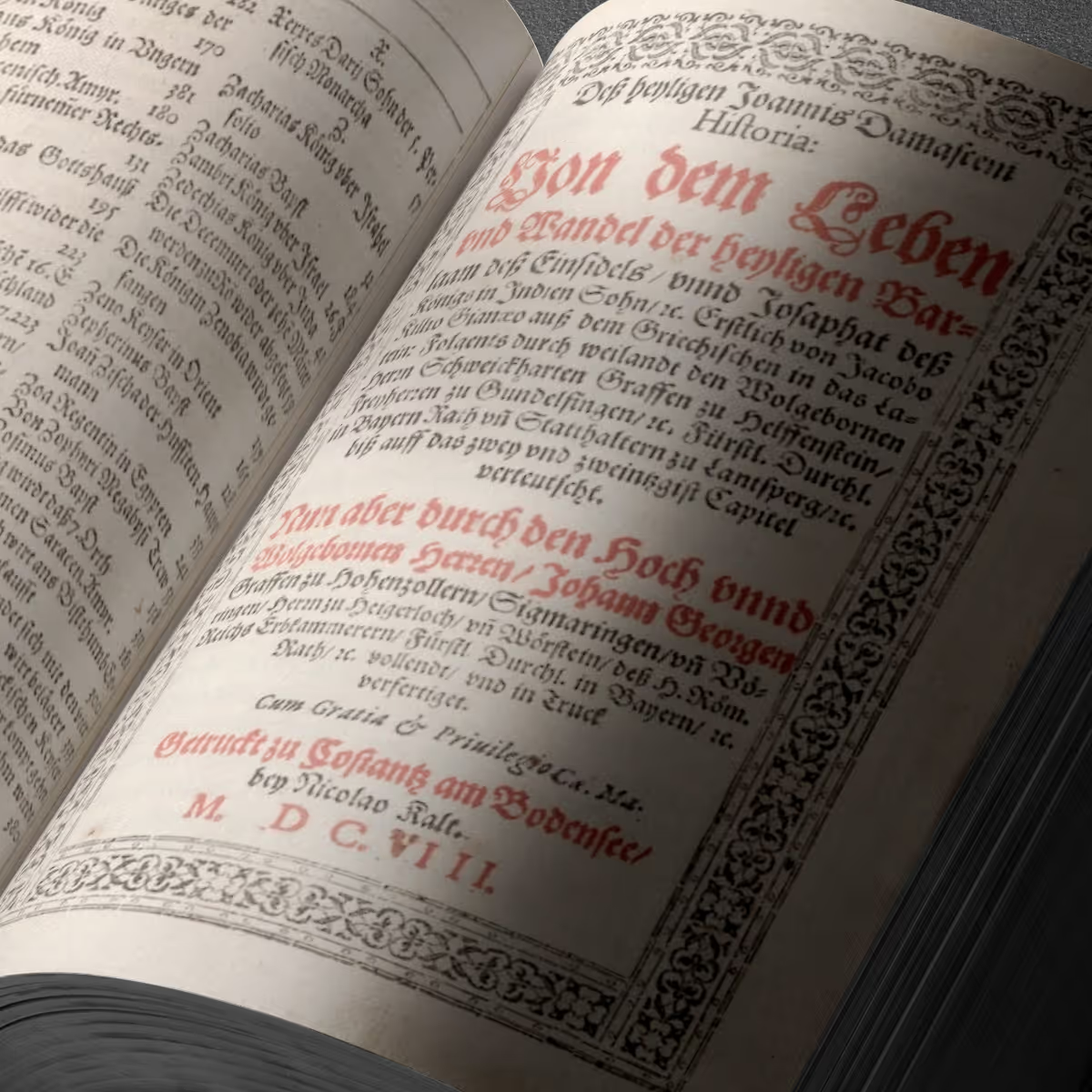

The European Renaissance illustrates the problem in striking detail. Nearly 70 percent of Renaissance-era printed books remain undigitized, and over 95 percent of Latin works from the period have never been translated. These texts include foundational works in philosophy, natural science, medicine, mathematics, political theory, and humanist thought.

Though celebrated as the era that launched modernity, the Renaissance is largely invisible in the digital age. Without access to these texts, contemporary scholars and students encounter only a fragment of the period’s intellectual richness.

The Latin Corpus

Latin represents the largest untranslated corpus of Western thought. Over 200,000 early Latin works have never been translated, covering subjects from astronomy and law to medicine, alchemy, and theology. Most are not digitized or catalogued, and access is limited to specialized scholars. Latin texts were the primary vessels of knowledge for over a millennium, meaning that vast swaths of European intellectual history remain out of reach.

Beyond Europe: Gaps in Global Knowledge

The problem extends far beyond Western Europe. Across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, enormous collections of manuscripts remain inaccessible.

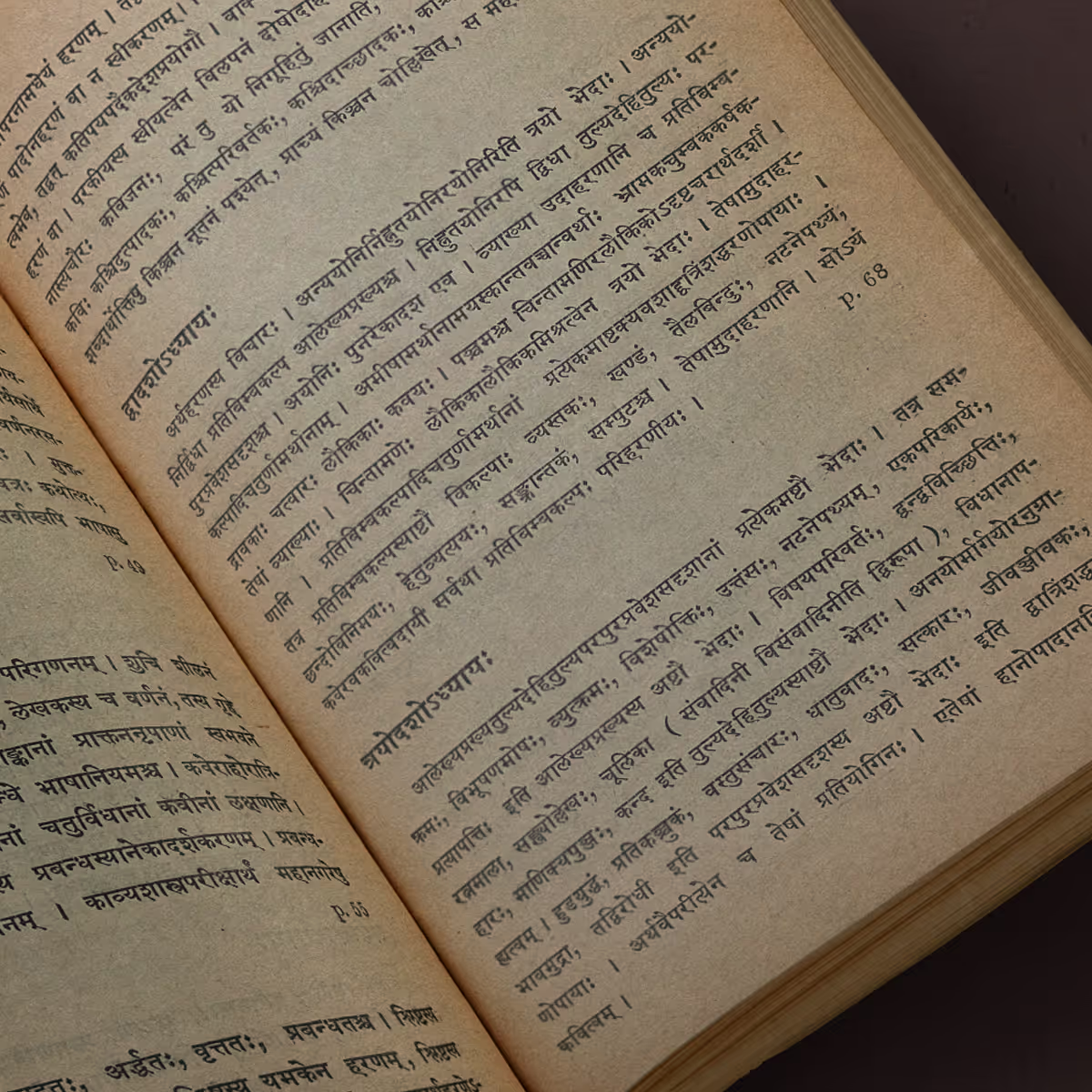

Sanskrit: India’s National Manuscripts Mission estimates roughly 30 million Sanskrit manuscripts exist, yet fewer than 1 percent have been critically edited or published. Translation into modern languages is even rarer.

Chinese: Classical Chinese literature encompasses millions of works. Less than 10 percent have modern annotated editions, leaving much of China’s intellectual heritage unreachable to contemporary scholars.

Arabic and Persian: Tens of thousands of works in science, mathematics, medicine, and philosophy remain untranslated. The majority are stored in private or uncatalogued collections.

African manuscript traditions: Timbuktu alone preserves hundreds of thousands of manuscripts, most of which have never been digitized or made widely accessible.

Every culture faces the same challenge: knowledge exists but cannot be read.

Implications for Humanity

The consequences of this inaccessibility are profound.

Cultural

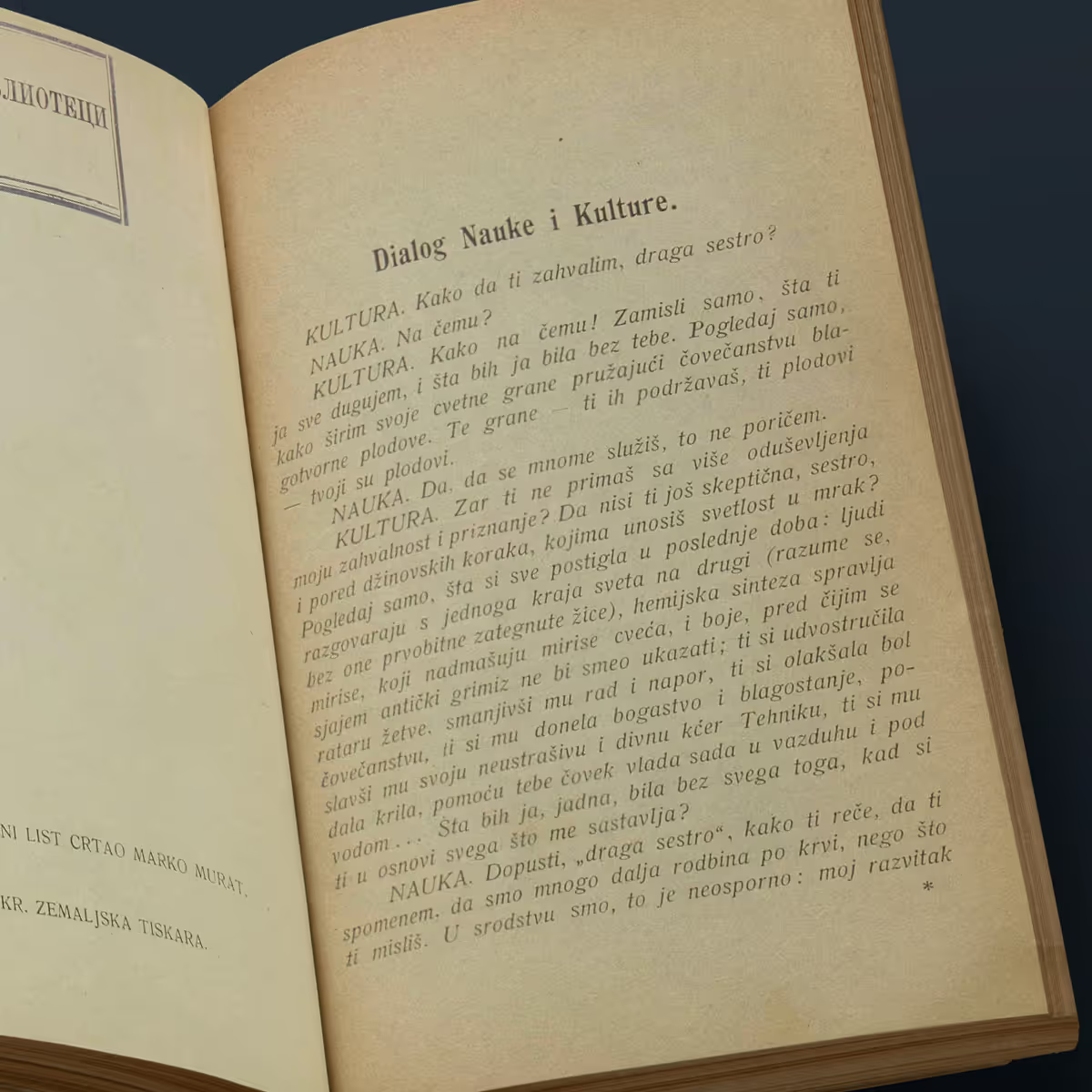

Civilizations lose connection to their own intellectual histories. Modern education and scholarship are built on partial evidence. Philosophical, scientific, and literary traditions appear thin or incomplete. Without access to original sources, interpretations of history are necessarily simplified or distorted.

Ethical

Communities whose texts remain untranslated are excluded from global intellectual conversation. Cultural heritage becomes unevenly distributed, reinforcing systemic inequities.

Civilizational

Fragile manuscripts are deteriorating faster than they can be preserved or digitized. Every book that remains inaccessible represents knowledge that could be lost forever. Societies risk building the future on incomplete memory, narrowing the intellectual horizon of generations to come.

The AI Disconnect

Artificial intelligence increasingly interprets and mediates human knowledge. Yet AI systems are trained on digitized and online sources. The vast majority of foundational texts from the Renaissance, classical Latin works, Sanskrit manuscripts, and other cultural corpora are missing from AI training datasets.

The result is a new layer of intellectual fragmentation. Machines that will shape education, research, and public discourse are learning from incomplete historical records. Innovations, reasoning, and ethical frameworks derived from AI are therefore based on a partial and biased dataset, even as AI grows more capable.

This does not mean AI is the problem. It highlights the urgency of making knowledge accessible for humans first—AI simply mirrors the gaps we have inherited.

Toward a Complete Human Record

Addressing this gap requires a global commitment to digitization, translation, and access. Preservation alone is not enough; texts must be made readable, searchable, and usable. Every manuscript and book liberated from obscurity strengthens the collective understanding of human thought.

Digitization and translation are cultural infrastructure projects, akin to building libraries for the future. They ensure that scholarship, education, and technology are informed by the full spectrum of ideas that shaped humanity. Making this knowledge accessible is not just a scholarly mission—it is a civilizational imperative.

By bridging the divide between what exists and what can be read, we reconnect with the breadth of human thought. Each text recovered is a step toward restoring continuity in human knowledge, giving current and future generations the tools to innovate, question, and learn from the past.

%20(1).avif)